The results of an investment (in an early-stage startup) depend not only on the success of that startup, but also on the form of the investment.

A sophisticated investor is going to be nodding right now, thinking about liquidation preferences and other common add-on’s to equity investments. But at the same time, those sophisticated investors likely have a majority of their investments in a state where they are worth somewhere between nothing and a 1x return. A state often called a “zombie” investment.

The root cause of “living dead” investments is not the high failure rate of startups. Failure leads to truly dead companies. These zombies are not only still running, but earning revenues or even profits.

The actual root cause is the traditional structure of equity investments. Take a step back and look at the assumptions of such deals:

- Investors buy P% of the startup for $X

- The entrepreneur uses $X to earn $R

- If $R is sufficiently large, an acquirer buys the company, returning the investor $10X

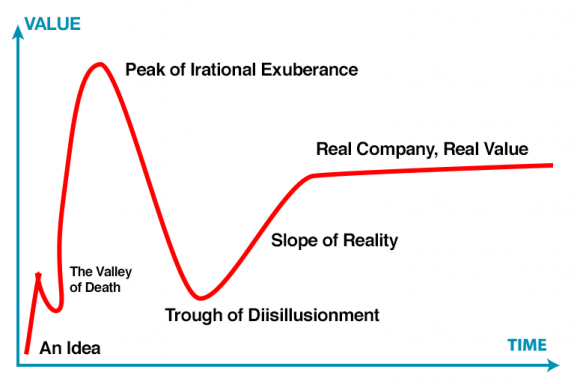

This is the basic formula for success as an Angel or venture capitalist. The problem is that successful investors only see this story play out 1 out of every 10 investments, plus 2 investments with a $5X return, a few more with a $1X return, and 4 or 5 that are total losses. Unsuccessful investors never see the $10X, and without that, have a loss across their portfolio.

I look at this and wonder why the investment structure is optimized for the least likely case, rather than the most likely case. Is there not an alternate investment form that boosts the returns of the majority of deals above $1X?

Traditionally, the only other form of investment is debt. It works for homes, cars, Fortune 500’s and the U.S. Treasury, but traditional debt does not provide enough reward for the risk of early-stage investments. When debt terms are adjusted for investors, the results are too much risk for entrepreneurs.

Looking around the fringes of the financial world, I found a structure that does work. Revenue-based financing (a.k.a. Royalty-based financing). This comes in a variety of forms, but in general it works like this:

- Investors provide $X

- Entrepreneurs use $X to earn $R

- Investors receive Z% of $R, until a total of $2X-$4X is returned

The two main variables here are the percent of revenue (Z%) and multiple of return. Typically the revenue-share is 3%-9% of “top-line revenues”, a metric that is easy to define and compute. The multiple is commonly $2X for growth-stage investments, and $3X-$4X for early-stage.

This basic structure provides a few benefits for investors. First, it provides a built-in “exit”, one that doesn’t wait until the entrepreneur has build up enough value to either attract an acquirer or launch an IPO. Second, it aligns investor interest and entrepreneurs, earn revenues. Third, it makes no assumptions about when the revenues will arrive, nor requires negotiation on when to issue dividends. Fourth, it leaves the company management free to operate in whatever manner they please, e.g. management worries about growth vs. profits. Fifth, it eliminates “zombies” as either companies are alive and earning revenues, or dead (or soon dead) earning nothing.

In short, it provides a reasonable payment for the use of investor capital, while providing a relatively high IRR (with a big boost of that IRR due to the quicker repayments vs. equity). Plus this structure boots the odds of at least a $1X return, as the investee begins repayments as soon as revenues are earned.

The drawback? The upside of the investments are capped. If the structure asks for $4X, then the maximum return is $4X. However, there are multiple fixes for this issue: tack on some warrants, or toss in some traditional equity. Do something that adds back in some of the upside.

I discovered this structure while researching the business model for Fledge. Fledge, in addition to a business accelerator, is also an investment fund, one that targets “conscious” companies, a market with few exits and few comparables. Fledge uses RBF for its investments, roughly as described above, and so far after 19 such deals, we think it’s not only the right structure for impact investing, but a potential fix for the broken venture capital market everywhere.

Makes perfect sense. Is the real reason investors are greedy? They’d be totally unwilling to miss out on the 1/100 rocket ship that returns 100x by hedging their bets with royalties. That is my gut reaction, but I’d be curious to hear what traditional angels think about this. Certainly there are types of businesses (probably ecommerce) that this makes a lot of sense for. I wish there were more funding options for startups, this seems like an ideal one.

[…] incentives don’t change. They don’t worry about 100% loss of their investment as a zombie. They can instead either live with what might be a slower rate of repayment and thus a lower rate […]