Protect the whole team from each other.

The biggest mistake in splitting equity is not in the percentages. It is in the structure of the equity itself. Specifically, the biggest mistake is that, too often, at the end of the conversation, the people around the table are granted shares with no restrictions.

The proper way to structure all initial equity is in the form of “restricted shares.” These are typically common shares, but with one legal restriction: the company has the right to repurchase the shares at their initial value until the restriction is removed.

RULE 5:

Founders’ shares should be granted as “restricted shares”.

Before I discuss the best way to set up restricted shares, let me illustrate why restricted shares are needed.

Hypothetically, imagine that you and a co-founder start a company. Your partner has 51% of the equity and you have 49%. Three months later, your partner has a crisis and quits. You are now stuck in a position of trying to create a successful, valuable company, but one in which more than half of the equity is owned by someone who is no longer working toward that success.

With restricted shares, the company can buy back those shares, even if your co-partner doesn’t want to sell them. Your ex co-partner must sell those shares to you, if you ask, and must sell them at the initial price. With those shares erased from the equity split, your percentage ownership (along with all other owners) will increase by the percentage of shares being repurchased, redistributing equity to those who continue building value in the company.

A more common hypothetical is that you get excited about bringing in an early employee, perhaps someone who has a great track record in sales at a big company. You entice this star performer to join your startup with 15% of the equity, dropping your share to 85%. Six months later, after no sales, you discover that this person simply can’t handle life within a startup, an environment without the support provided at that large company. You fire this employee (with a generous severance package), but are left with a minority shareholder who is likely to be bitter about those lost six months.

With restricted shares, in both these cases, all or part of that equity grant can be repurchased by the company, eliminating the ongoing ownership issue.

The key to making this work is a pre-determined formula for removing the restriction on the shares over time.

Here is how it typically works. Each grantee is given N shares of restricted shares. The restriction is removed from one-forty-eighth of those shares monthly for four years (forty-eight months).

RULE 6:

The restriction should be removed in increments over the next four years.

There is nothing magical about four years. It is simply the norm expected by investors and, in the modern world, it is a reasonably long time horizon to expect any person to commit to work for one company.

Optimized for Taxes

This mechanism of issuing restricted shares and then slowly removing the restriction is financially equivalent to the shareholder receiving small grants of unrestricted shares. The reason for what seems like a backwards process (i.e., granting restricted shares and then slowly removing the restriction) is to minimize the tax liability. The IRS considers grants of stock to be income and taxes the value of those shares even though shares themselves are difficult or impossible to sell.

At the beginning, the price of the initial shares is usually set at $0.01 or $0.001 or even $0.00001. The tax implication of this initial grant of shares is usually minimal. And as these shares are restricted, the tax implications are, in reality, a bit complex, as the IRS considers the removal of the restriction to have taxable value, unless the founders have filed for an “83(b)” election. Talk to your tax accountant or attorney to ensure you are doing this paperwork correctly.

As the value of your shares increases, this “unrealized value” is not taxed (at least not in the U.S.), i.e., you owe nothing as the value of your shares increases, until the day that you sell those shares.

Without these tax rules (e.g., if you are incorporated outside the U.S.), it may be simpler to skip the restricted shares and just grant the founders small grants of unrestricted shares that eventually add up to the full, unrestricted stake. However, one other important benefit of using restricted shares is that other shareholders may be added in the future, such as investors or future employees. Having the founders’ shares set aside in large, restricted blocks settles those ownership claims very clearly up front, at the start of the business. This removes the risk that the grants will be renegotiated as investors or others join in the ownership pool.

More, Later

That said, if the company survives its initial two or three years, it is possible at that time to readdress the equity positions of the still-active employees, including you. In other words, there is no need to try to predict the next five or seven or ten years of value in each employee and in the company as a whole. For now, the equity split should focus on the work accomplished to date and on the expectations of work in the immediate next few years.

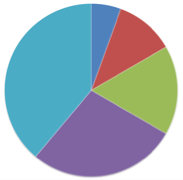

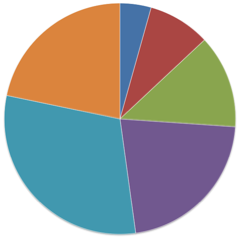

There is only 100% of the total equity available to split today. However, it is possible later to add more equity to this pie. That may seem complicated, but, in reality, it is quite simple. When adding equity, each owner is simply “diluted” by an equal percentage, creating space for new owners or grants of shares to existing owners.

Ideally, the value of each share rises more than the amount of dilution, making the shrunken percentage worth more than the original, larger percentages. Whether true or not, the key to remember is that this initial split of equity is not necessarily the last discussion on the topic.