You have a decision to make. If you have seconds to decide, you go with your gut. If you have minutes, you might take that minute to weigh Plan A with Plan B. If you have weeks you might create a pro-con list to help decide between those two – or even three – options. If you have months, you might take the time to brainstorm for some out-of-the-box options.

What most people overlook is that there is always another option.

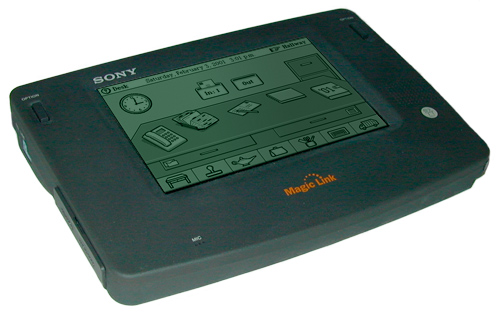

My favorite example of this dates back to my first startup. To 1993. Before the Internet. Way before smartphones. Before the first popular handheld device, the Palm Pilot.

Do you remember the Palm Pilot? Do you remember Graffiti?

Well… long story short, my startup had a working version of that a year before Palm. If we hadn’t showed our software, Scribe, to Palm, the Palm Pilot probably would have had a keyboard instead of Graffiti.

In any case, we also showed Scribe to General Magic (a spin-off of Apple with a handheld device different from and earlier than the infamous Apple Newton). We offered to license it to them. With that, they had the chance to be the Palm Pilot years before Palm pivoted from software to hardware.

That didn’t happen because of two What If’s? First, General Magic was months away from shipping, with Sony and Motorola eager to get their devices into the market with no further delays. What if this better, faster, quicker input system was included instead of an on-screen keyboard.

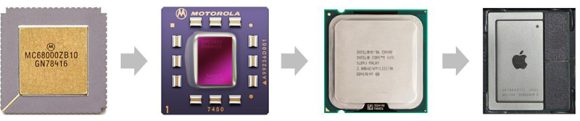

Second, we needed to agree upon the terms of a license. They didn’t want to pay us for every unit sold, and we didn’t want to leave $1 million on the table by licensing the software for a flat rate. At this same period of time, my little software company had agreements from both Sony and Motorola for $1/unit royalties for software embedded on their devices to receive faxes, plus $1/unit royalties for the software on each of their add-on cards that allowed the devices to receive messages over the paging network. (For those of you under 40, faxing and paging were the email and texting of the 1990s.)

In the end, we never came to terms. Sony and Motorola shipped. Not many units sold.

Six years later, two startups later, at 3am one night, I’m trying to fall back to sleep, and a thought occurs to me on how to structure the license. We should have traded off the per-unit royalty for shares (or warrants) in the then-private General Magic company. The company was owned by Apple, Sony, Motorola, and Panasonic. If we believed it would sell millions of units then we should have believed the value of the shares would follow the scale of units sold.

My business partner and I didn’t understand how startup equity worked in 1993. Six years later, 1999 was near the peak of the dot-com bubble, and by then everyone in software (thought) they knew how equity worked.

That option never even crossed our mind in 1993. Maybe best for the world, as Palm may have never shipped the Pilot if the Sony and Motorola devices had a Graffiti-like input and still failed. But financially not great for me, as General Magic’s IPO was the first hugely overpriced IPO of the dot-com era.

There is always another option, even when you think every option has been considered.

Originally posted on my new Substack, whatifonly.substack.com