Income inequality has finally floated to the surface of the news. It’s nice to see this issue being talked about, but much of what I’m seeing is focused on the symptoms, with solutions like “just pay the workers more”. What I’d prefer are some opinions on the root causes, purposefully plural as this is not a simple issue.

I believe I have uncovered one such hidden cause. It lies down in the deep underbelly of capitalism, and thus you may need to put aside some of your most beholden thoughts to consider it. The cause hides within a simple question:

Why does equity last forever?

To answer this question, let me take you back to 1903. In 1903, Henry Ford founded the Ford Motor Company. This was not his first car company, but his third. The first two failed. With those failures, Henry’s new investors insisted that he outsource production to John and Horace Dodge, already famed manufacturers, and the brothers themselves invested $10,000 (1902 dollars) in Ford’s startup.

The Ford Motor Company was an instant hit. Ford sold 2,000 cars in its first year, 100,000 cars by 1907, over 500,000 in 1915. In modern terms, a hit like the last decade at Apple and Google and Facebook, combined. Huge growth, and huge profits.

Back in the early 1900’s, unlike today’s high-growth companies, the norm was for companies to pay out at least 80% of their profits as dividends. Henry didn’t much like investors, and preferred reinvesting profits for growth, paying out a “miserly” 46% of Ford’s profits (on average) between 1903 and 1915.

Despite being miserly, the total payouts in those 13 years was $55 million. For John and Horace Dodge, with their combined 10% ownership, they received a total of $5.5 million (1915 dollars).

$5.5 million on a $10,000 investment, a 550x return.

Before you go compare this to the Apple, Google, and Facebook IPOs, do note that upon receiving their $1.6 million dividend check in 1915, the Dodge brothers still owned 10% of Ford’s company. The story gets more interesting in 1916 with $60 million in profits, which could have meant another 600x return in that year alone, but that is a story for another post.

With this “real life” case study in mind, back to income inequality, and the question at hand. Why is equity eternal? What justifies annual dividends after the initial investment capital has been repaid multiple times?

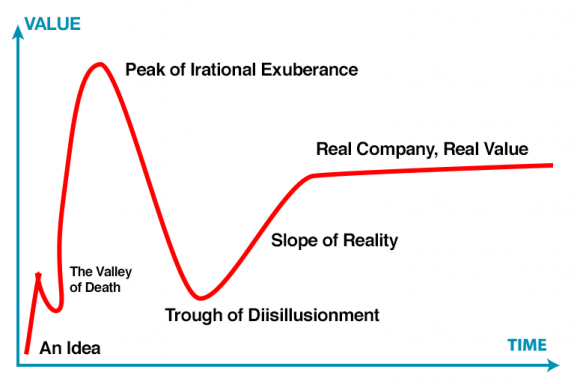

The common answer is that equity is risky, and thus requires a high reward. I’ll accept that, but what risk is worth a 550x reward? Or a 100x reward? Certainly, if there is only a 1 in 100 chance of even a 1x return, then the reward should be more than 100x. With those odds, given 100 investments and all outcomes being 0x or 550x, the average return should be 5.5x. Clearly, given most investments have lower returns, the risk must be lower than 1 in 100. What are the odds for early-stage investments?

In the seminal study of returns to Angel investors, Wiltbank and Boeker show that across the 500+ investors and 17 years in their data set, the average return was 2.6x in 3.5 years, for an IRR of 27%. They further show that the successful investors included at least one investment with a 10x or higher return, which occurred in only 7% of the investments in the data set.

Which means that for an individual investment, given a sufficient set of deals to pick from and sufficient due diligence, the odds of picking a big winner is about 7 in 100. Risky, but only when you consider that single investment. When you instead look at portfolios of early-stage investment, Kevin Dick, analyzing the same Wiltbank/Boeker data set shows that with a portfolio of 100 Angel-sized, the odds of seeing a positive return are nearly 100%. And with 200 investments, the odds are you will double your money. (Past performance and incomplete data is not necessarily indicative of future results).

So… if the odds in early-stage equity investments are not 1 in 100, why do the investors get a chance to earn a 100x return? The odds are far better than 5 in 100, making 20x seem like too much. In the Wiltbank/Boeker data set, the odds are in fact 48 in 100 of returning at least a 1x, almost a 50:50 coin flip.

Let’s go back to 1903. What if John and Horace had lent $10,000 to Ford? Ford could have easily repaid the loan in a year or two or three, paying a 27% interest rate, equal to the Wiltbank/Boeker IRR. With its success, Ford could have easily paid 30% or even 100% in interest. After a few years at any of those rates, the debt would be repaid, and the debt retired. Retired, as a key difference between debt and equity is that debt is not forever.

Quickly, let’s talk about debt. The justification for debt is that the borrower is “renting” capital, and that the timeframe, risk, and market set a price for that rent, which takes the form of an interest rate. As both the capital and rent are denominated in dollars, this price of capital is not always obvious. Charge rent in a different currency and it becomes obvious. For example, I lend you $120, you each month you pay me $10 (repaying the principal) and give me a chocolate bar (the rent). After a year the $120 has been paid back ($10 x 12 months) and in exchange for the use of my $120, you’ve paid me 12 chocolate bars. Or in other words, the cost of my $120 in capital was 12 chocolate bars.

Within this in mind, the original question can be reframed as, what is the cost of capital in an equity investment?

In those terms, the cost is infinite. Not only did Ford continue to pay dividends in 1916 and beyond, the shares Henry sold his investors back in 1903 are still outstanding, available for your purchase on the NYSE. If you go buy a share right now, next quarter you will receive a $0.50 dividend, and you can continue to do that for as long as you’d like, as long as the company doesn’t go bankrupt, or stops paying a dividend. At the current price and dividend it will take 30 quarters (6 years) to be paid the $15 price for your share, but like Horace and John, that share will still be yours after that.

This is true for any of the 500+ publicly traded companies that pay a dividend. Most of these companies are profitable, hence the dividends.

My claim is that this eternal equity, infinite cost of capital is a key cause of income inequality. I claim that this is the root cause that makes capitalism look greedy. I claim this is a flaw in the system that unduly rewards the people who have capital, overpaying them for the use of that capital, at the expense of those that are creating the value.

To my capitalistic ears, that last sentence sounds far more like Karl Marx than Adam Smith, but none the less, after thinking this through, it seems to me to be correct. From this claim, unlike Mark, my logical conclusion is not to throw out ownership, nor even throw out equity, but to modify the traditional equity investment structure to set a risk-adjusted cost to that capital.

We live in an age of big data. We can analyze the history of investing and determine actual risks. From that, we can negotiate a reasonable “rent” for the use of capital. And with it, we can end the era where the capitalists earn unlimited capital from the use of their capital, giving a chance for the 99% to catch up.

If Ford had paid a lower ‘rent’ for capital, how would that have reduced inequality? He would have had more, his investors less. If the goal is equality, that’s not it.

I agree with your criticism of well-intentioned but overly simplistic solutions. Sadly, if we rule out simplistic analyses what’s left is the complex, unequal and occasionally corrupt interaction of willing buyers and willing sellers.

If you believe my conclusion, then there is of course another question about potential infinite returns to founders. I have another set of logic for that answer that is too long to fit into a short reply.

Meanwhile, what we do know from Henry is that he was likely to take the profits and reinvest them into the Ford company, rather than pay out any dividends. That would have created more jobs and spread the wealth far more to employees than investors. Remember, 46% of Ford’s profits were given to the “owners” rather than employees and vendors.

We also know that Henry loved to lower prices. So it is also likely that the price of Ford cars could be have lowered more than they were. That would have left more wealth in the hands of the customers, who eventually were the employees and the rest of the middle class.

–

That’s an interesting thought. The position of “The Economist”, which is my main source for economic info is that increase in inequality is being driven by increasing returns to capital, and this increasing returns is presumably due to technological change. See for example http://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21594264-previous-technological-innovation-has-always-delivered-more-long-run-employment-not-less

Obviously the near infinite upside of equity amplifies the return to capital.

Assuming that your math adds up, which I can’t comment on, one thought is that at the level of the whole economy the losses due to dud investments may be a lot larger than they are in your figures. Not saying that you aren’t getting those margins, but it may be that a lot of investment doesn’t turn out to be that profitable. One way to put this theory is that there may be a lot of investors that aren’t as good as you are.

Basically what you’re saying is that founders ought to be able to get a better deal in their financing, with a bounded payback. There’s nothing to stop you from trying to arrange a deal like that, of course, but why would anyone want to take you up on that?

Debt is an established bounded obligation, but we have much more negative views on defaulting on debt vs. equity.

I also wonder, if the effect you propose is true, how big this effect is on the whole economy, given that (in my impression) the vast majority of the investment flow is in large companies with much less growth potential.

@robamacl, http://humancond.org

Most startups fail, but despite that fact, most early-stage investors do earn a profit. This is true of both venture capital and the averages for Angel investing. Meanwhile, up at the end of the equity market of public companies, at least in the U.S., no 20 year period in the last 100 years did not see a rise in the value of public equities. Thus at the level of the whole economy, we can safely assume that equity investing has a positive return on capital.

In terms of bounded investments, I run a fund that uses such a structure, and here in Seattle we’re seeing quite a number of investments that take a form that in general is being called a “structured exit”, which focuses primarily on a capped return.

As for your final comment, the effect is huge. My assertion is that there is no justification for nearly all of the public equities. I’m asserting that those share should have long ago been retired via some form of redemption. How many more dividends must Ford pay? Or U.S. Steel? Or Boeing? Or Pfizer?

If I ran Apple or Google or any of the public companies sitting on huge hoards of cash, I’d not do small share buybacks, but instead offer every shareholder a buyout, over 10 or 20 years, until every public share was retired.

Remember, those public companies make no money when their shares are traded. Yes, they made money when those shares where issued, but that money should have long been invested, and long been returned with some multiple. What justifies those shares still being traded 20 or 50 or 100 years later?

So, if I start a company, invest $10,000 and develop a killer iPhone/Android app that generates $1 million in the first year, declining in subsequent years and then as it ages still generates $10,000 a year for 50 years, I should be capped on my return? Of course not. But if I invested $5,000 and another person invested $5,000, with the same results, we should be capped? Who would get the remaining return? Extend this simplistic analysis to employees who hold stock options, and the premise continues to fall apart. Both investment and worker compensation are free markets. Anything less is classic socialist redistribution. Not saying that is good or bad, but the logic needs to be straight.

How about if you start a company, stay long enough to vest some shares, and then leave? Do you then think it “fair” for that person to continue earning some of the profits forever?

I’ll flesh out my thoughts on the value of sweat equity in another post. They do not include “redistribution” like I’ve seen in any socialist or communist country.

Meanwhile, I find it interesting that both you and @disqus_fMWNpbakTd:disqus skip past the question of the value of capital, and jump straight to the value of founder’s equity. Although those two pieces of ownership look similar and act similar, they are not at all identical. Those two types of owners provide different services two the company and often have different expectations of returns from those services. The founders provide their “sweat” in terms of building and/or sell product. The investors provide capital.

Yes, in some cases the founders also provide capital, and when I advice teams on splitting equity, my advice is always to separate out that capital into a separate part of the negotiation, making the value of that capital distinct from the value of the person.

Finally, yes, I very much agree the solution needs to fit the market of willing buyer and willing seller. In this case, traditional and momentum seems to have blinded entrepreneurs to view the trust cost of the capital they receive from investors. Or perhaps the flaw is that investors are the experts on investing, and thus the market flaw is an information asymmety which allows the investors to get a better deal than they deserve.

How about if you start a company, stay long enough to vest some shares, and then leave? Do you then think it “fair” for that person to continue earning some of the profits forever?

It depends how the capital was created. If the capital was derived from providing valuable work in the economy then yes, if it was derived through an inflation mechanism like fractional reserve banking then no.

In practical terms, one would need to manage a company it is

only possible to leave a company and extract profit forever if one makes exceptions to the definition of a monopoly. In a truly free market a competitor would undercut your ability to extract profit forever while doing nothing.

I laud your quest to understand the causes of rising inequality, but I’m afraid I don’t accept your analysis. In your calculations of the return on Angel investments, you simply assume “Sufficient due diligence”. I believe that Angel investors do significant work in analysing and selecting companies to invest in; they also do significant work after their investment in advising the companies in which they have invesed. So some of the rewards they receive should be regarded as earned income, rather than return on equity. If you want to discuss excess returns to equity, you should consider normal equity, as traded on the stock exchange: numerous studies on this type of investment show that the returns on equity average slightly more, over the long term, than, for example, the interest available on straight loans to the government.

You illustrate your discussion with the Ford Motor Company, at the start of the last century. But I believe equality was increasing for the first half of that century, and the basic concept that “equity is forever” applied then as now. My perception is that inequality was traditionally very high: If you go back to the middle ages, Kings, Lords and the like were extremely rich, the vast majority were very poor. If you go back further, the vast majority of the population were serfs, property of their lord. So equality within countries improved over centuries until sometime around 1970, and since then the trend has reversed. Of course, over the last thirty years, there has been a great improvement in the wealth of some of the poorest populations (e.g. China), so we have to be careful with our definitions.

Broadly, if we are seeking reasons for the rise in inequality over the last 40 years or so, we should ask what changed 40 years ago.

Intuitively, I believe technology is at least part of the explanation for the rise in inequality: If you hire translators, one competent worker is similar to another. But if you find someone who can program a computer to do your translations, they are worth a multiple of what an individual translator is worth to you.

Another possible explanation is world peace. Wars tend to disrupt the status quo, make arbitrary (i.e. random) reallocations of resources, and strengthen the hand of governments to tax and expropriate wealth. Peace allows wealth to accumulate and be passed on from generation to generation.

Rather than increasing in the first half of the 20th century, income inequality actually increased steadily until 1914, then decreased slightly until 1920, then increased steadily again until the outbreak of WWII. Income inequality only seriously declined, though, in the 1950s and 1960s, as the effects of the capital destruction during WWII and strong economic growth and unionization in the 1950s caused a significant reduction in income inequality across the western world. Income inequality started to increase again in the UK from 1975 or so, in the USA from 1980, and in most of the rest of the western world from the 1990s on.

I use the Ford case as it so clearly shows a return on capital that has no reasonable justification. How can a few hours of due diligence be worth $5 million?

The Dodge Brothers certainly took a risk. They certainly may have lost their $10,000. I’m fine if they had received $100,000 for that risk. You might talk me into $200,000 as reasonable. But after that, their return is usurous. They did nothing more to earn the next $100,000, nor the next $100,000, nor the next next next next next $100,000, 50 times over.

Do note that I specifically in this post do not propose who that money should go to. I’ll get to that in a future post. My goal of this post is to point out the oddity of the system as exists today, where “ownership” is forever, and from that structure, returns to owners are perpetual and uncapped.

That structure inevitably provides unearned returns to the capitalists, creating more capital which leads to more returns. These funds must come in lieu of higher wages to the workers and lower prices to the customers. Either way, this system redistributes cash to the capitalists, for the use of their capital, which can only lead to inequality, short of war, taxes, or depression.

“My claim is that this eternal equity, infinite cost of

capital is a key cause of income inequality. I claim that this is the root

cause that makes capitalism look greedy. I claim this is a flaw in the

system that unduly rewards the people who have capital, overpaying them for the

use of that capital, at the expense of those that are creating the value.”

What if the response is a combination of a few approaches… equity in a company is ownership in the company. Ownership is always long term and the expectation is

always that you will earn a return on your investment for the longterm, after all,

you have created an ‘offering’, service or product. This offering is created

perhaps initially by you the business creator, and then as you have grown you

have provided jobs and income to others aka employees. Perhaps this is where

the perspective needs to change. And while you can say just pay employees more,

perhaps it is significantly more – treat them as owners and see the continued

growth in prosperity for all stakeholders. Employee owned organizations, and

even co-ops, tend to perform better financially in the long run because there

is commitment at all levels. While the CEO may not make mega-millions each

year, they and others will make more over the longterm. And the other question

to ask is “How much is enough?” with respect to CEO pay. A car company CEO

recently gave himself an 11% raise moving his salary band from $23m to $25m

+/-. Employees did not get a raise – this is problematic on at least 2 level;

1. Employees will disengage in terms of productivity, waste management etc, 2. How much is enough? The message must be directed to CEOs who behave in a

corporately unethical manner forgetting who actually generated the long term

wealth and sustainability – it was not and cannot be done single-handedly as

many ‘heroic’ managers (Mintzberg) would like to believe.

Ttl;dr: —The cause of Wealth Inequality lies in the source

of the capital as defined by the Cantillon Effect.—

Thanks lunarmobiscuit, Wealth Inequality is one of the biggest systems of a larger problem facing our society today. You have touched on a rather abstract aspect of the capital but the actual causes are far more acute and obvious. I believe it was Richard Cantillon who first described the problem you address with investment capital as analysed in his experience in John Law’s Mississippi Company.

I don’t share your proposed solution as I believe Cantillon Effect, aptly names after Richard Cantillon identifies the problem at its source as opposed to mitigating it with technology as you propose.

*The problem is all about the quality of the capital and where

the capital comes from.*

“Why does equity last forever?” can be answered as follows: because 2 people and their heirs voluntarily agree it should, and then we create laws to make it so.

In the real world, not the environmental parasitic world we live in (paradoxical sharing the same causes as Wealth Inequality), wealth comes from doing work others in the economy value. Risk is the very real chance that members in the economy may not value that work in the future. We have set up laws to mitigate that risk, and they come at a cost, the cost is Wealth Inequality and the loss of

environmental capital to exponential growth.

The situation you describe is John and Horace Dodge, own 10% of the entire Ford motor company’s profits, and because they have a 10% stake in the equity, and as the profits of the Ford motor company increase, the get a return that exceeds their investment in an absurd way. This is not considered problematic it is in fact how our system works, there is a problem if Ford motor company, is granted a monopoly that would prevent competition; this could be the granting of a patent for example. This problem would use the law to ensure absurd profits. IP being another debate entirely.

The Problem is when that equity is evaluated by the market, if the market believes a 5% return on investment is justified, then the equity could be valued at 2000% more than the dividend. So the problem arises when and only when the equity is sold, and only if the capital is created by banks, as opposed to capital created by savings form valued hard work and labour.

The capital created from fractional reserve banking, inflates the money supply, the result in wealth moves from the labourers who earns it last, to the Masters of money who create it ( an increase in Wealth Inequality) this is known as the Cantillon Effect. Effectively the banks launder fake (fractional reserve) money – a money substitute or currency) into the economy through John and Horace Dodge and earn dividends from Ford to prop up the fake value. The absurd amounts of capital now available to spend by John and Horace Dodge, can destabilises the economy as it could represent risk free investments in that from an entrepreneurial perspective the consequences of failure are insignificant given the capital available. In that capital that is not backed by valued work, is used to fund projects that may otherwise not be viable.

At $16.50 a share who is to say the rich must be the only ones to share in eternal equity? Granted it will take a lot longer for the poor to grow their equity, but they do have an equal opportunity to take share in eternal equity. For those not willing to risk money on a single company, market ETFs represent an awesome opportunity to earn on the eternal equity of up to 100% of the U.S. equity market.

I argue that financial knowledge and informing people on the concept of compounding are more important to improving equality in income.

Government tax structure is also an issue. Why tax food such as fruits, vegetables, and meat, when we give subsidies to farm corporations that are huge with

“Four companies owning 43% of the commercial seed market worldwide

Four companies owning 83.5% of the beef market.

The top four firms own 66% of the hog industry.

The top four firms control 58.5% of the broiler chicken industry

while small farms continue to struggle to get by”

source: http://www.farmaid.org/site/c.qlI5IhNVJsE/b.8586841/k.382D/Corporate_Power_in_Agriculture/apps/ka/ct/contactus.asp?c=qlI5IhNVJsE&b=8586841&en=clKNK3NLJbJWJdMOLaKTJaPZImJQKaPWKmKXIdO4LvJdG

Large corporations also receive tax deductions on advertising and can out advertise any small business that gets into their market. Advertising has become a monopoly that is government supported with over $150 billion spent in 2013 with a high growth rate. Why not tax large companies on excessive advertising so that prices of goods go down and quality improves. Instead we tax labor, and raise taxes on labor, and then raise the minimum wage, leading to an increase in unemployment, creating an even greater income gap for those still unemployed.

The list goes on…

Equity structure is not the root problem, but a lack of knowledge on its benefits may be of substance

[…] capital instead of passively living off ‘financial extraction licenses’. This post on the founding story of Ford has more thoughts on the relationship between perpetual returns and […]

[…] one of our companies, we’re just fine with that. And in any case, I find that objection to be a flaw in our current capitalistic […]