By this definition we have at least 2.6 billion deep sinners – the 37% of people in the world who live on less than $2 a day. They are the future Steve Jobs’, Mohandas Gandhis, Madame Curies and Pablo Picassos who will instead eke out a living as drug dealers, child soldiers, prostitutes and destitute slum dwellers.

The three trillion dollars or more we have wasted in misguided development aid probably represent an even bigger sin. But it seems to me that the worst sin of all is our abject failure to achieve scale for the handful of projects that have produced measurable positive impacts on the lives of poor people.

How can we successfully achieve scale? It takes planning and designing from the very beginning, and the unleashing of powerful positive market forces at the locations where poor people are buyers and sellers. The only way to unleash those forces is to demonstrate to global businesses that they can earn attractive profits selling transformative products to poor customers. This is exactly what I have dedicated the rest of my life to accomplishing.

But, I am not an economist. How do some of the world’s leading economists view the prospect of earning sizeable profits serving poor customers at scale?

Is it immoral to earn profits selling to poor customers?

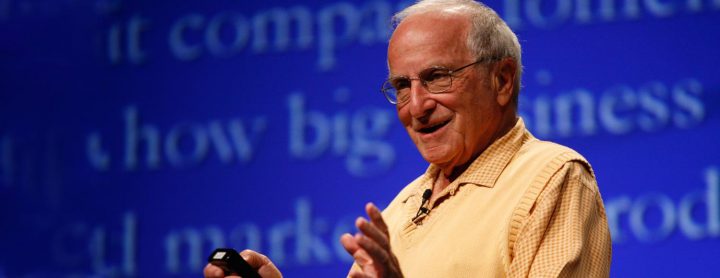

“No!” says Milton Friedman, the celebrated free market economist.

“…there is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game.” Friedman believes that a marketplace of enterprises earning profit within the rules is the most powerful lever to improve society.

“Yes!” says economist and Nobel Prize winner Muhammed Yunus.

“Poverty should be eradicated, not seen as a money-making opportunity.” Yunus believes that investors in social businesses should only get their money back. In my view, that adds up to a sizable interest-free subsidy, which is a constraint to scale.

Why do I believe that the answer to extreme poverty is to earn attractive profits serving poor customers?

The microfinance movement and the work of iDE combined have probably helped about 50 million extremely poor people move out of poverty. Even if we have helped 100 million poor people move out of poverty, this amounts to less than 4% of the 2.6 billion people in the world who live on less than $2 a day. This is pitiful!

I define meaningful scale as any strategy or initiative capable of helping at least 100 million $2-a-day people move out of poverty by at least doubling their income. We desperately need to find ways to bring to scale the few comparatively successful models for development that are available.

What are the common features of initiatives that have truly helped extremely poor people move out of poverty?

- They begin by thoroughly listening to poor customers and thoroughly understanding the specific context of their lives.

- They design and implement ruthlessly affordable technologies or business models.

- Energizing private sector market forces plays a central role in their implementation.

- Radical decentralization is integrated into economically viable last mile distribution.

- Design for scale is a central focus of the enterprise from the very beginning.

It is clear that all of these factors are integral components of a business system, but this takes us back to the original question: should it be a business system that enhances the livelihoods of poor people without making a profit for outside investors? Or should it make a profit for investors as well as the poor people who are served by it?

The only way for a business to help at least 100 million poor people move out of poverty is to follow the laws of basic economics.

To me the answer is obvious. The only way for a business to help at least 100 million poor people move out of poverty is to follow the laws of basic economics, which means providing an opportunity for both poor and rich investors to earn what they consider to be an attractive profit from their participation.

I have no doubt that there are huge profitable virgin markets all over the world serving $2 a day customers waiting to be tapped. By the laws of economics, creating a new market requires taking a very large risk, but the reward should be commensurate to the risk. If the new venture is successful, all the investors – the poor customer who buys the product, the shopkeeper who sells it, the company employee who makes or transports the product or manages the supply chain, and all the financial investors in the company – should make an attractive profit.

Here is an example: Coal contributes 40% of global carbon emissions and releases millions of tons of heavy metals and other pollutants every year, worsening climate change and sickening people around the world. Properly carbonized biomass can be substituted for coal and co-fired alongside it in proportions up to 80%. The world’s farmers produce four billion tons of agricultural waste each year. If 100 million tons of this agricultural waste could be effectively and affordably carbonized in decentralized rural settings, a multinational enterprise finding a cost-effective way to make it happen could reach global sales of $10 billion a year within five to ten years. Such a company would not only provide attractive profits to investors willing to take on the substantial risk involved, but would furthermore double the incomes of at least 100 million $2-a-day enterprise participants in developing countries.

The only way a company like this can reach scale is with the financial backing of for-profit venture investments. And the only way to justify those comparatively high-risk, early-stage investments is if the company provides the opportunity to make exceptionally good profits if it succeeds.

We have two options:

- One is to keep hoping that governments will come through with billions of new aid dollars, keep asking individuals to dig deeper for charity dollars, and hope that the low-or-no-profit venture capital space takes off and becomes a truly global phenomenon. We could plod along full of hope but low on results, celebrating increases in impact of fractions of a percentage point.

- The other option is to blend the designer’s sensibility, the artist’s creativity, the ground-level aid worker’s understanding of local context, and the entrepreneurs’ dynamism and drive for success, and create profitable global companies that serve poor customers with products and services that help them rise out of poverty. We could unleash the full power of the greatest force in human history – profit – and start ending poverty by the hundreds of millions.

It would be immoral to do anything else.

The author of this post, Paul Polak, has brought 20+ million farmers out of poverty. His work is dedicated to designing products for the 2.6 billion customers who live on less than $2/day. Read more of his opinion in The Business Solution to Poverty.

Paul is right – it’s simple economics. Material capital will flow to the highest bidder – that is, to the opportunity with the highest risk/reward ratio. In order for these firms to function at truly meaningful scale, they will need to be competitive with other investment opportunities. In this context, it’s ‘immoral’ and short-sighted not to design these firms with an appropriate risk-adjusted return in mind.

I’m afraid that Mr. Polak hasn’t chosen the best example to illustrate his opinion. The issue of (who pays) the costs of giving up at cheap polluting energy in undeveloped world is a sensible one in the context of actual dispute on (reducing) global warming. And there is a strong current of opinion that it is ethical the developed countries to pay (more) for the global positive effect of replacing these polluting energy sources with others “greener” but more expensive.

Regarding Mr. Yunus position, I believe the social economy is meant to provide missing services and goods for (poor) people there where the free market doesn’t. As long as people accept and can afford to buy goods and services that include a large trade margin (that ensure the attractive profit for investors) there is no need of social economy. But if people can’t afford -or simply they don’t accept- to pay for this profit there is room for social entrepreneurs to provide needed goods and services at affordable (but sustainable) prices.

[…] original post can be found on the site of Michael “Luni” […]