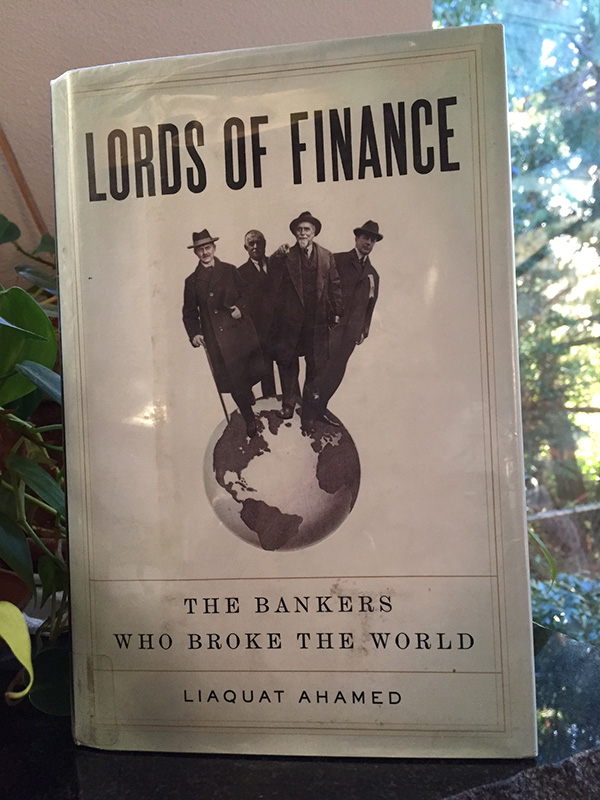

Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World continues my research into wealth inequality and the real-world workings of capitalism. This book is the story primarily of four men: Norman, Strong, Moreau, and Schadt, the heads of the central banks of the UK, U.S., France, and Germany in the 1910’s through 1940’s.

continues my research into wealth inequality and the real-world workings of capitalism. This book is the story primarily of four men: Norman, Strong, Moreau, and Schadt, the heads of the central banks of the UK, U.S., France, and Germany in the 1910’s through 1940’s.

These are the men who restructured the financial world at the end of WWI, when all the countries of Europe were financially insolvent, when the center of finance of the world shifted from London to New York. And these four men were still in power as the Great Depression swept the world, and some still in power at the start of WWII.

There are two big lessons of this book, and they are scary.

1- Economics isn’t just the “dismal science“, it’s far from any science at all. During WWI, all four of the world’s big economies had left the gold standard and starting printing as much currency as needed to pay for the war, with no regard to inflation. At the end of the war, they sat down and basically negotiated amongst the three winning countries to split up the gold reserves, interest rates, and foreign exchange rates, based on politics and posturing, not based on any tested economic theory.

2- These decisions and others that followed came from the creativity and persuasiveness of the men in the room, along with the Presidents, Prime Ministers, and Premiers who had to agree to some of these terms.

The world experienced a moment similar to this in 2007-2008 when Ben Bernanke, Hank Paulson, and President Obama literally sat in a room and decided which banks and which companies would be saved, which would be handed to new owners, and which would be liquidated. Three men, one room, and a good chance that a bad decision would wipe out trillions of dollars of someone’s wealth, if not tens of trillions of dollars.

Personally, I find that a scary thought, as after 100 years of central banking in the U.S., it still seems like the people in charge simply make a best guess and hope it all works out.

The book talks about the times when it didn’t work out. The German reparations of WWI, which was not a minor factor that led to WWII. The Great Depression, which had no single cause, but instead a series of horrible decisions in all four countries.

The book also explained a few great decisions. The story of the hyperinflation of the German Mark is often told, but this book is the first explanation I’ve seen that actually explains how that hyperinflation was stopped. It was a central banker named Schadt, sitting in an office that was formerly a storeroom, paid nothing for his work, with that work mostly being talking on the phone to influential Germans followed by the introduction of the Rentenmark, a new currency backed by a new property tax. A currency unlike any I’ve come across before, but no doubt one studied by the two Wall Street economists who in 1994 introduced the Real in Brazil to fix that country’s bout of hyperinflation.

Showing how one person can chance international banking and finance explains how Paul Volker in the late 1970’s can seemingly single-handedly end American stagflation.

Or how, as this book finishes up with, John Maynard Keynes and Harry Dexter White (along with hundreds of lesser-known helpers working through the details) can spend a few weeks in a resort in New Hampshire and walk away with the creation of the modern international foreign exchange system, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the pieces of what would later be the World Trade Organization.

As an optimist, my take away from this book is that one person, in the right place at the right time, with sufficient power or access to power, can truly change the world. Let’s just hope these people in power make good decisions when the next global crisis comes along.