The idea of anti-trust by government is not yet 130 years old, and it took a decade before President Teddy Roosevelt to put those ideas into action. The last time the U.S. government broke up a monopoly was AT&T in 1982.

The Curse of Bigness by Tim Wu gives a quick background on how anti-trust all began, then dives into the key questions:

- When is big too big?

- How do we measure big?

- Is Anti-Trust positive or negative?

- Why have there been no big breakups in almost 40 years?

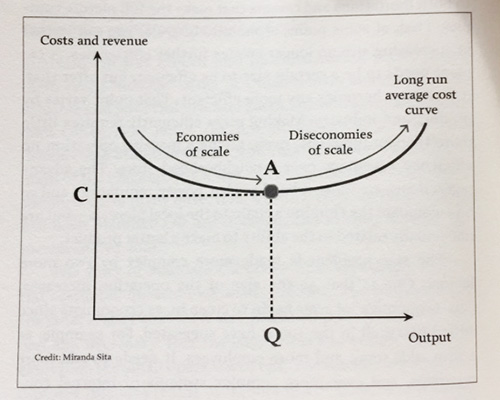

Before getting into that, Wu ask the most pertinent questions, “Is Big Better?” For that he included a diagram I had never seen or thought of before, the Diseconomies of scale:

I know from my experience as entrepreneur and work with startups that new, small companies thrive for economies of scale, as small is a hindrance in that regard. I know from my brief stint at IBM, from years selling to Fortune 500 companies, and from Dilbert and The Office that large companies are incredibly inefficient.

Wu writes: It is true that a large factory, operating at volumn, will usually produce goods at a lower cost than a mom-and-pop operation. This is why cars are built on large assembly lines, not at the neighborhood craft automobile manufacturer. In the age of Amazon and Google, it often seems that the company which as the most servers or collects the most data necessarily has the better product. But at some point, economies of scale “run out”… varying by product and industry. Making pizza efficiently requires little more than an industrial oven, giving a massive operation no efficiency advantage over a neighborhood store.

So why do companies grow beyond the sweet spot in that efficiency curve? Because management cares about power and power grows with size, even if efficiency drops. Because competition is troublesome, and if the government lets a company buy its competition, those troubles go away. Because that sweet spot isn’t obvious to owners, managers, workers, customers, or government, and thus we get caught up in the anti-trust debate only after companies grow well beyond peak efficiency.

President Teddy Roosevelt and his successor President Taft were long enough ago that most of us don’t remember what they did for anti-trust, nor far enough ago that their efforts are taught in history. Roosevelt is known for breaking up Standard Oil, but that was just one of 45 cases he filed. Taft filed 75 cases. There were a lot of monopolies created in the Gilded Age and dozens of learnings about how monopolies effect markets that rarely, if ever, get discussed.

Standard Oil was the biggest of these “trusts.” In 1911 the U.S. government broke up the company into 34 pieces. Did the country run out of oil? No. Did the smaller companies go bankrupt? No. In fact, the value of the 34 pieces collectively doubled in value within a year and rose five-fold within five years.

If you are old enough, you might remember AT&T in 1974. It employed over 1 million employees. It was the largest and most valuable company in the U.S. It was a proud monopolist, touting that only an efficient monopoly could provide reliable telephone service. That monopoly crushed innovation. It wasn’t until after the breakup in 1982 did faxes, the internet, and mobile phones take off as popular services.

The next biggest monopoly in the 1970’s was IBM, and while the government spent decades researching a break-up, that anti-trust action was limited to a “consent decree.” That “policeman at the shoulder” most likely helped created the PC industry, as IBM didn’t use its well-honed anti-competitive machine in that market, but instead licensed chips from Intel and software from Microsoft to create the IBM PC.

The book ends diving into Judge Robert Bork and his influence on anti-trust that continues today. His 1978 book The Antitrust Paradox, focused the U.S. government’s definition of anti-trust to focused solely on prices customers pay.

This is why as the U.S. airline industry, mobile phone providers, and cable TV providers all consolidated to three or four competitors, the government did nothing but approve merger after merger, as prices didn’t rise until years after the mergers were approved. This is why in the current debates, the free services from Google and Facebook don’t fit the anti-trust debate, as free doesn’t fit into Bork’s definition of monopolistic practices.

All in all, the book is a good primer on monopolies, anti-trust, and has a lot more to say than in this brief book report. I highly recommend picking up a copy if you want to better understand what has gone wrong in American business and how we might go about fixing it.