Last week I posted a TL;DR blog post on why the Fledge accelerator works so well at helping startups succeed. In short, a few key elements of its program, along an enormous number of tiny details learned through iteration and experimentation.

This post is inspired from the multitude of conversations I have with people and organizations who want to help startups and who often have an idea on a program they’d like to create, but who typically have no experience operating, mentoring, or observing business incubators or accelerator to know what actually works.

The big problem, for both them and the tens of thousands of startups participating in the existing programs is that there is very little published about what truly works and what just feels good to startups at the time, and thus most programs at best do the latter.

Let me share some of my six years of research and five years of experience in the industry to help separate feeling good from doing good. Or more to the point, how to most efficiently help startups, as a lot of the programs provide more applause than actual, long-term assistance.

Business Plan Competitions

The business plan competition is a staple of universities, foundations, and others who use such programs to bring some excitement to their supporters… at the expense of the participants.

If there is one simple change we could make to help entrepreneurs, it would be abolishment of the business plan competition, the one style of entrepreneurship program that does more harm than good.

Why? Because it claims to separate the “winners” from the losers, but does this with a set of criteria that has nothing to do with actual business success, which is measured by revenue from customers and profits. Neither do competitions use the common proxy for early success, investment by investors. Instead, business plan competitions tend to pick the best told story, regardless of its viability as a business.

I’ve been a judge at dozens of these competitions. I’ve spent hours deliberating which teams to send forward into the next round. I’ve helped my own students and fledglings win, using my judging experience to teach them what to say to get picked.

Winning certainly feels good, but competition winners generally don’t have any higher chance of actual, long-term business success. In fact, the more typical pattern is that the winners of the university business plan competitions tend to have a higher chance of failure. The runners up tend to outlast the winners.

For the masses of competitors, everyone always says it was “worth it”, as they do after any organized bit of coaching/mentoring. I personally would rather give a team an hour of free mentoring outside a competition, saving them the angst of competing and the black mark for not winning.

And I’d far rather volunteer a few hours of my time to run a workshop of a whole roomful of entrepreneurs, rather than spend that time reading their 1-sheets in preparation for judging a few hours of pitches.

Business Incubator

Another classic model of startup assistance is the government-funded startup “incubator”, where companies are invited in for 6, 9, 12, 24, or more months to build their budding businesses. Often the space is provided for free (or at least subsidized). Often a coach or two is thrown in as well, meeting with the team once per month. Sometimes these workspaces have lawyers and accountants, web designers, marketers, etc. in-house or on-call to help out as well.

I’ve found such programs in cities across the U.S., Europe, and into the developing world. They are so commonplace you’d think there was a study from the 1970’s showing how government grants into such programs generate huge streams of taxes or 99% of all new jobs or some other incredible statistics.

Personally, I’ve never heard of any well-known startup coming from a program of this form.

From my experience with accelerators, these programs seem to be missing everything that makes an accelerator actually work: Formal education, mentor whiplash, and artificial deadlines, to force action to happen, plus an incentive structure to get the company out the door, on its own feet yet still supported by the program.

Day/Weekend/Week-long Training

At the other end of the startup help spectrum are the day-long, weekend-long, and week-long entrepreneurship training programs. I’ve run more of these myself over the past five years various lengths to keep count.

I think of these as opportunities to give entrepreneurs a kick in the pants. Often a kick (or strong shove) is needed to push a concept along between idea and reality. Often entrepreneurs get stuck, not knowing the next step (or a next step) in that process. A bit of training is often sufficient to move the idea forward.

These events always feel good, both for teacher and students. Entrepreneurship is a very complicated topic, and thus there isn’t a one hour, or four hour, or even four month class that can cover it all.

Training along isn’t sufficient, but it is none the less useful, especially if taught well, especially if it helps entrepreneurs avoid the most common repeated mistakes.

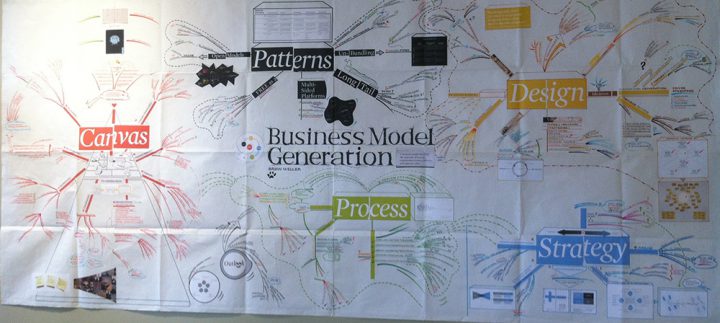

I wish there were more of these programs in more places. I suspect there isn’t primarily because the startup world is greatly lacking a good variety of books that teach entrepreneurship. The Lean Startup is a good book, but its only scratches one corner of one surface. The same with Business Model Generation. These are each covered in just one of my standard ten lectures when I teach entrepreneurship at Fledge, and two of twenty five lectures in my full MBA class at Presidio Graduate School.

Classes lack the excitement of a competition, and the lack of photo-ops by government officials and donors like incubators. None the less, they work, and we need more of these.

Co-working

Five years ago co-working spaces were a new idea. Today, in cities like Seattle, New York, London, and even Nairobi, there are dozens of co-working spaces to choose from. For startups, these are useful, as they provide an affordable place to operate a business, some community support, and if nothing else, a place to feel like you are doing business, rather than always working at home or always mooching space off of the neighborhood coffee shop.

In terms of startup assistance, they are at best frameworks where more useful entrepreneurship programs can operate. The coworking itself is just a tiny baby step toward helping startups succeed. Startups need mentoring and training, and co-working spaces are great places to find such programs, unrelated to the walls, desks, and chairs of the co-working business model.

Mentors

Startups need mentors. I can’t praise the idea of mentor whiplash enough as I’ve seen few other startup assistance tools work as well. Too people know this.

Outside of accelerators, the most common pattern for mentorship is “Office Hours”, held either within a co-working space (and another example of why those spaces are useful) or at a startup training event. These are nice, but far from reaching the scale of mentor whiplash.

It seems too often mentors think that their single opinion should be sufficient for a startup, and thus mentorship sessions don’t typically end with recommendations for more mentors, like they should. Plus first-time entrepreneurs don’t naturally seek too much mentorship, and thus they don’t press mentors for such introductions, as they really should.

If we treated mentoring like we do networking, more entrepreneurs would see the benefits.

Conclusion

It’s not that all these styles of assistance don’t help startups. More advice shared with more startups is good. The problem is that some programs are far more efficient than others at disseminating that advice, and startups all have a limited amount of time to succeed.

We thus should be aware of whether we are maximizing the use of an entrepreneur’s time when we volunteer our own time to provide help for his/her startup.

Too little of what is done for startups keeps that in mind.

[UPDATE: I expanded on this post and published that even longer TL;DR into a new book, The Next Step for Communities: Teaching Entrepreneurship]