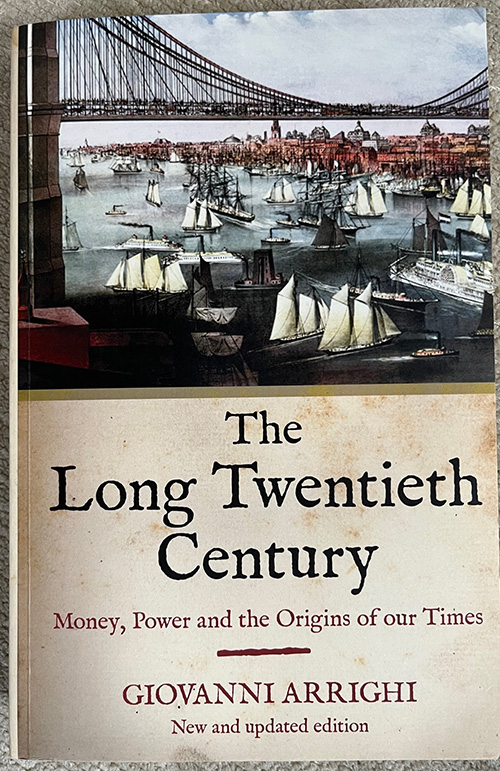

The Long Twentieth Century is more than its name describes, a very long and detailed economic history of not just the 20th Century but global Western capital of four eras: Venice/Genoa, Dutch Empire, British Empire, United States.

TL;DR, with an emphasis on the don’t read… the interesting part of this book isn’t the 20th Century nor the Long 18th Century either, as both of those eras are much better explained elsewhere. What is interesting is the deep dive into global trade and finance back in the 1400s through 1600s when the financial capital of the world was Antwerp and and then Amsterdam, hundreds of years before it moved to London and then New York.

I don’t know whether it is the American bias that commonly leaves out that history, or some re-written history by the British that make it sound like the British Empire was the first global empire, but prior to this book if you had asked me about the Dutch Empire I would not thought them more powerful than Spain or England in the 1600s and if you asked me how the Dutch managed to be a powerful economic force from Europe to Asia, I might have guess tulips. This book never bothered to mention tulips, as they played no role.

Instead the story starts in the 1400s with the rivalry between Venice and Genoa, the two most powerful governments in the Mediterranean at that time, both due to sea-based trade, both due to managing the European stage of what was then a global trade route from China, India, and Southeast Asia that reached all of Europe.

Most of modern finance was invented in that era. Most of the riches gathered by Spain in the New World were managed by bankers from Genoa, based in Antwerp in modern-day Belgium, in what was then part of Hapsburg-rule Europe, as was Spain. Spain also ruled Netherlands at that time, but after almost a decade of resistance the Netherlands gained their independence, started taking over Portuguese outposts in Africa and Asia, and eventually took over in global trade from the Iberian powers.

Netherlands in the 1700s then lost out of Britain in part because rich Dutch merchants ran out of Dutch-run companies to invest in, and started backing British merchant companies. Part was the British innovation of taking over large swaths of the foreign lands, instead of the Dutch practices of only controlling strategic ports.

For example, how did New Amsterdam on the island of Manhattan because New York? Why are we not taught about the first big battle fought a century before the Revolutionary War? Simple, there was no battle. One British navy ship arrived in New Amsterdam. That ship had more cannon, guns, and soldiers than the whole colony, and thus the colony simply surrendered without a fight.

The Dutch colonies were about business and trade, not conquest. This is why the British Empire is better known and in terms of land area, vastly larger.

For the end of the British financial rule of global trade, the better books to read are War and Gold and Lords of Finance, both of which have reviews on this blog.

I read these incredibly dry economic histories not because they are page turners. They are often painfully dry, and this book is perhaps the driest of them all. But I push my way through as there tends to be an interesting tidbit or two in these books that are overlooked by the popular history books.

An example of what I mean by dry (in case you feel like joining me in this rare hobby), and what is by far the most succinct paragraph in the whole book. Page 247, paragraph one of the part 4, which is the first moment we hear about the 20th Century in a book with that in the title:

The strategies and structures of capital accumulation that have shaped our times first came into existence in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. They originated in a new internationalization of cost within the economizing logic of capitalist enterprise. Just as the Dutch regime had taken world-scale processes of capital accumulation one step further than the Genoese by internalizing protection costs, and the British regime had taken them a step further than the Dutch by internalizing production costs, so the US regime has done the same in relation to the British by internalizing transaction cost.

It took the previous 246 pages to explain what the first two thirds of that is supposed to mean, and then 90 pages more to explain the last part. Or in short, TL;DR.